Green buildings around the globe

From a glass house in Connecticut to a sustainable school in a Balinese jungle, how cutting-edge architecture also draws on age-old traditions.

Cutting-edge, sustainable architecture around the world is the subject of new book Green Architecture by Philip Jodidio. Experimental perhaps, but many green buildings today tap into age-old traditions of harnessing heat through orientating them towards the sun, or by gaining thermal mass through use of thick stone or mud. The book also celebrates technological ways of controlling global warming caused by construction, which s for a high proportion of greenhouse gas emissions. Here is a selection of its projects, from the monumental to the modest.

Panyaden School, Thailand

Ally Taylor

Ally TaylorChiefly influenced by nature, Dutch practice 24 Architecture created a layout inspired by the tropical staghorn fern for this primary school in Chiang Mai. The building broadcasts its ecological aims through its extravagantly organic form, use of locally sourced materials and low carbon footprint. Its low-hanging, undulating, Gaudíesque roof – ed by columns made of fast-growing, ultra-sustainable bamboo – seems to hover above the floor, which is made of rammed earth.

Ospedale dell’Angelo, Italy

Enrico Cano

Enrico CanoThe 680-bed Ospedale dell’Angelo in Venice-Mestre, a 40-year-long project completed by Italian architect Emilio Ambasz, is billed as the ‘world’s first green general hospital’. Defying the stereotype of institutional architecture, the 30m (100ft)-high, 200m (650ft)-long entrance hall incorporates a gargantuan winter garden, overlooked by half of the patients’ rooms and by lounges on each floor. Outside the windows of the remaining patients’ rooms are plant-filled containers. And the operating rooms, laboratories, service facilities and parking areas all have green roofs.

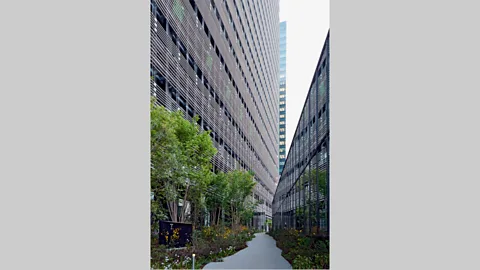

Sony City, Japan

Yutaka Suzuki

Yutaka SuzukiSony City in Osaki, Tokyo, is Sony’s research and development department and was designed by architects Nikken Sekkei, who say it was conceived as a massive cooling device that performs like ‘a natural forest’. Solar s projecting from the south façade that generate heat double as devices shading Sony City from strong sunlight. The building is clad with Bioskin, an external layer of ceramic tubes that cools the exterior when rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the tubes. As the water evaporates, it cools the tubes and adjacent air.

Glass/Wood House, United States

Kengo Kuma & Associates for Glass Wood House

Kengo Kuma & Associates for Glass Wood HouseKengo Kuma, the Japanese architect known for sympathetically connecting buildings with nature, was entrusted with renovating a glass-fronted house designed by John Black Lee in 1956. The Glass Wood House is in New Canaan, Connecticut, and Kuma disrupted the symmetry of the modernist box by adding an L-shaped extension that projects into the forest without imposing on the landscape. “We created a major change by getting rid of the house’s symmetry and covering its exterior with wooden louvres,” he says, adding that the renovated house now has a “mild” transparency that has superseded its 1950s “isolated” translucency.

Japanese pavilion, Italy

Iwan Baan

Iwan BaanFor the 2008 Venice Architecture Biennale, architect Junya Ishigami designed the Japanese pavilion comprising small glass houses around the building in the park, Giardini della Biennale. Ishigami referenced Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition in London of 1851. Tables and benches for public use were dotted around the garden in an ambiguous blurring of indoor and outdoor space. The glass houses’ ethereal quality was emphasised by delicate drawings hung on white walls.

Chen House, Taiwan

Lukas Casagrande

Lukas CasagrandeIndoors and outdoors are connected in this farmers’ shelter with an extensive wooden deck in the Datun Mountains, Taipei. Designed by Finnish architect Marco Casagrande, it has a slatted front, that allows cool breezes to enter in warmer months. The porous facade brings daylight into the interior, while a simple fireplace keeps it warm. It is raised off the ground to protect it from occasional flooding. “The house is not strong or heavy – it is weak and flexible,” says Casagrande. “It does not close the environment out but gives farmers a needed shelter.”

Ecoboulevard of Vallecas, Spain

Emilio P Doitzua

Emilio P DoitzuaThis monumental, 22,500-sq-m (240,000 sq ft) proposal for an urban pavilion in Madrid was dreamt up by Spanish architects Ecosistema Urbano, who refer to it as an “air tree”. Designed to stand in the centre of a busy avenue, surrounded by trees and filled with tiers of vegetation, it provides an oasis of coolness during the city’s oppressively dry summer months. Its temperature is lowered inside by tiers of vegetation and water vapour generated by solar s that makes the space eight to 10 degrees cooler than the street outside.

U6 Penthouse,

Frank Hülsbömer

Frank HülsbömerCreated by German architects Heberle Mayer, this idiosyncratic, low-cost addition to an existing building in Berlin – on previously unused roof space – is made using a greenhouse manufactured by French firm Filclair. Planning restrictions vetoed covering the entire roof, resulting in an outdoor terrace used in summer, where a mobile kitchen can be placed. In winter, the transparent structure is ively heated by sunlight, although an inner layer of curtains made from a heat-reflecting fabric and large sliding doors prevent the interior overheating.

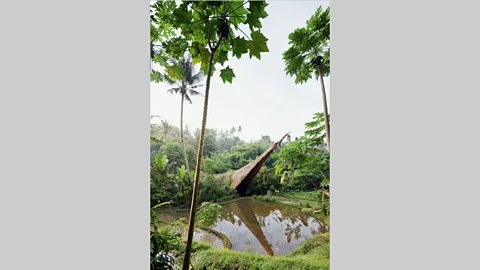

Green School, Indonesia

Iwan Baan

Iwan BaanAn arresting, primeval-looking structure in the thick of the jungle in Badung, Bali, announces the presence of this experimental school, which educates its pupils about sustainable materials. The building’s open sides connect it with the outdoors and an open-plan interior encourage natural ventilation. The project was conceived by design-and-construction company PT Bamboo Pure, which uses bamboo, and the Meranggi Foundation, which establishes bamboo plantations in Indonesia, distributing the plants to local farmers for free. Other parts of the school were constructed using recycled rubber and car windshields, while its grounds boast an organic garden and fences made of living trees.

Green Architecture by Philip Jodidio is published by Taschen