The last film poster painter of Taiwan

After 48 years of immortalising Hollywood legends, one of the world’s last film painters is now partially blind but vows to continue ‘until I can no longer see’.

Yan Jhen-Fa has never met a film star, but he’s painted so many he can’t them all. Nearly every day for the last 48 years, the 66-year-old artist shuffles onto the pavement across from the Chin Men Theater in Taiwan’s oldest city, Tainan, holding a small image and five buckets of paint.

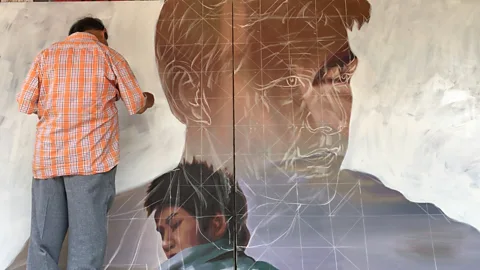

For the next eight hours, he squats on a plastic stool and kneels on the ground in his makeshift outdoor studio, using deft brush strokes to depict film legends in surreal, film noir-like friezes of suspense, ion or pride. When he finishes, he clambers up the scaffolding and uses rope to hoist the 20-sq-m canvases three storeys into the air to hang them on the theatre’s facade.

Today, the Chin Men is the only remaining theatre in Taiwan to continue the age-old tradition of displaying hand-painted film posters. And in an era of digital printing and computerised billboards, Yan is one of the last artists in the world carrying on a craft that’s on the verge of extinction.

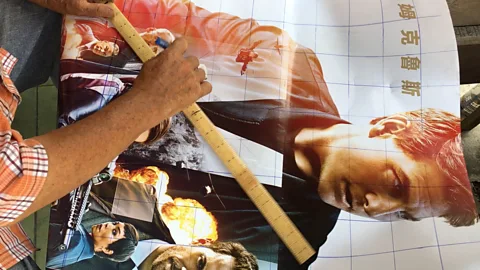

On a recent afternoon, Yan toiled away in the sweltering heat as a stream of pedestrians breezed by the ageing artist. With the precision of an architect and the flair of an Impressionist, Yan patiently sketched over last week’s work with a line-ruled grid before bringing Tom Cruise to life for the new Mission: Impossible film.

With each sweeping stoke, the slight man with eyeglasses began filling the giant canvas with billowing explosions, snow-capped peaks and larger-than-life heroes, villains and sidekicks. Layers of light and shadow immortalised actors in a glamorous glow, and the vintage-style affiche evoked the golden age of the silver screen.

“I’ve painted thousands of films in my lifetime, but my name has never been in the credits and I’ve never signed my work,” Yan said quietly, crouching over a kaleidoscope of paint tins. “Still, in some small way, I feel like I’m a part of the movie production.”

As long as there have been movies, there have been movie posters. When silent films became popular in the 1910s, theatres around the world hired artists to convey the excitement of new releases and capture an audience’s attention before they even stepped into the theatre. By the 1940s, Hollywood studios began printing and shipping their painted posters around the globe. But in many places where skilled labour remained cheaper than billboard-sized prints, handmade paintings continued to adorn cinemas for decades to come.

In India, Bollywood employed 300 artists to decorate the country’s theatres with dramatic renderings of princesses and maharajahs for much of the 20th Century. In Ghana, local artists painted movie posters on flour sacks that could be rolled up and taken to the next screening until the 1990s. And in Thailand, Myanmar (also known as Burma) and the Philippines, artists scaled bamboo ladders to paint stills of films’ most memorable scenes and characters until the late 1990s.

But perhaps nowhere did this artistic tradition run deeper than in Taiwan, where gigantic oil-painted posters were once some of the most eye-grabbing sights on the island’s streets.

During the heyday of kung-fu movies in the 1970s, we had more than 700 theatres in the country, and almost every one employed its own artist. Now, Mr Yan is the last. He is a very important treasure of Taiwanese cinema,” said Chen Pin-Chuan, director of the Taiwan Film Institute.

Shy and softly spoken, Yan has always worked alone. It takes him two to three days to complete a painting, and ‘it all starts with the face.’ If he likes the film’s digitally printed poster, he’ll recreate it in a massive, dream-like portrait. If he doesn’t, he’ll sit in the front of the empty theatre and watch the movie. Then, he’ll carry six canvas s that each dwarf him out into the natural light and blend his own style with the film’s plot to ‘try to honour it in a new way.’

Having never married, Yan views painting as his life partner and pours himself into each portrait. Yet, while the Chin Men’s paint-splashed marquee has become one of Tainan’s most popular attractions, for many years the paint-speckled artist working across the street went unrecognised and unnoticed.

“Often when people by, they look at me and don’t believe I painted these. It makes me feel sad,” Yan said. “But when I see children look up at the theatre and get excited, I’m reminded of myself as a child and I smile.”

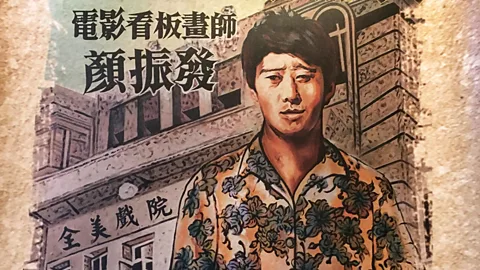

Yan (pictured in this self-portrait) grew up in a strict household on Tainan’s outskirts. He re studying film ads in the newspaper as a nine year old and recreating them with chalk. By 13, he was spending more time in Tainan’s cinemas than its classrooms – sometimes watching seven films a day and going home to sketch his favourite scenes from memory. When he finally told his parents at age 18 that he wanted to become a film artist’s apprentice, they chased him out of the house with a broom.

“They said I’d starve,” he ed. “And they were right.”

Yan apprenticed under one of Taiwan’s greatest billboard masters, Chen Feng Yun. For the first two years, he earned the equivalent of just $6 per month, surviving on soup and rice and sleeping in the theatre because he couldn’t afford to rent a flat. Instead of instructing Yan, the master merely let Yan observe him as he worked. Yan studied how the master gripped his brushes, memorised his colour combinations and practiced relentlessly. Then one day, something clicked.

“Everything has an essence, and you have to understand the subject’s essence to bring it to life,” Yan said. “It’s the blending of light and shadow, the person’s eyes and the angles that make it come alive.”

Soon Yan began begging his teacher for work, and whenever the master had too many commissions, he’d hand extra projects off to Yan. During the peak of Taiwan’s film industry in the 1970s, Yan hand-painted a staggering 100 to 200 billboards a month. Yet, in 1983 – 13 years and thousands of billboards after Yan first entered the master’s studio – a theatre manager revealed to Yan that the master had been ing all of Yan’s paintings off as his own for the past decade.

“I felt so taken advantage of, so invisible,” Yan said. “For many years, I received no credit for my work. But when the managers learned that I was the one behind all the paintings, I started working for every theatre in Tainan.”

In recent decades, the rise of DVDs, on-demand streaming and multiplex cinema chains has caused many old theatres in Taiwan to shut their doors. That, along with the cheap cost of mass-produced prints, has forced those that have survived to abandon the tradition of hand-painted posters.

Today, only a handful of theatres around the world still employ a full-time poster artist: there’s one in , one in Greece and one in the Philippines. And in Tainan, which once employed more than 30 full-time poster masters at the start of the 1980s, the Chin Men Theater has been Yan’s last and only client for the past 26 years.

“There has always been a hand-painted artist here and so it’s important that this culture doesn’t disappear, like it has everywhere else,” said the Chin Men’s manager, Wu Jyun-Cheng. “In the malls now, they use computers to print posters, but it looks dull and dead. Master Yan’s art is vivid and alive.”

Not much has changed at the Chin Men since Wu’s father opened it in 1950. Instead of computer-generated tickets, a teller still stamps each entry by hand. Inside, a sign politely asks men to remove their caps and an arrow points people downstairs to the air-raid shelter. Outside, Wu’s brother drives an old lorry through the streets, advertising the theatre’s latest releases with a bullhorn. And throughout the lobby, framed portraits of hometown hero and director Ang Lee serve as a shrine to the Chin Men’s most famous patron.

“It was this theatre where Ang Lee first fell in love with cinema as a young student, and he’s always said that the painted billboards were a big part of that attraction,” Wu said. “We are committed to keeping this tradition alive for as long as Master Yan is able.”

In the past year, images of Yan’s hand-painted posters have started circulating online. After working in the shadow of his famous master for so long, the once-anonymous artist has begun receiving praise from people he’s never met – including one Hollywood legend who Yan has spent much of his lifetime emulating.

“I am completely amazed by this man’s wonderful work,” said artist Drew Struzan, who has designed more than 150 hand-painted film posters – including ET the Extra-Terrestrial and the Indiana Jones, Back to the Future and Star Wars series. “The sheer scale he’s working with, the energy and ion he has, it’s beautiful. I’ve never seen anyone doing anything like this.”

While Yan continues to fight his lonely battle against digital printing one brushstroke at a time, the Chin Men Theater can only afford so many canvases. As a result, with each new film release, Yan has to paint over his old work and lose it forever – but not before snapping a photo of it hanging the theatre’s facade as a final keepsake.

A lifetime of painting has also exacted a punishing toll on his eyesight. Years ago, doctors discovered severe injuries to his retinas, and while they were able to repair his left eye, he has lost nearly all sight in the right. Surely, if a little more slowly these days, Yan soldiers on, insisting, “I’ll paint until I can no longer see.”

Since the last of his contemporaries abandoned the profession years ago, Yan recognises that Taiwan’s hand-painted cinema tradition is likely to disappear with his eyesight. So, after nearly 50 years of immortalising stars, Yan has spent the past four years instructing students.

Now, every weekend a group of 10 to 15 apprentices eagerly wait in a car parking across from the Chen Men Theater until their master arrives on his rattling purple scooter. Armed with easels, chalk and paint, Yan patiently teaches the group how to carve a canvas into triangle grids, how to mix five cans of paint into thousands of colours and how to search in a subject’s eyes to find their ‘essence’. He’s not sure if any of his pupils will follow in his footsteps, but he’s quick to impart a lesson he learned from struggling anonymously under his own master long ago.

“Don’t give up, don’t get discouraged,” Yan said, looking up at the theatre’s hand-painted canvases. “Every new film is a chance to capture someone’s attention.”

Custom Made is a BBC Travel series that introduces you to custodians of cultural traditions all around the world.